Article 20: The Book That Was There

The Book That Was There

Ben Huizenga - Round Table Member #047

When I was seven years old, my parents moved from the two flat on Melrose avenue, the one they'd been sharing with another couple, to the house on Waveland and Pulaski where they live to this day. There was a small room on the top floor, with ugly wood paneling and a rickety closet, which was now 'mine'. Both my sister and I were mucho pleased not to be sharing a room anymore.

Whoever my parents bought the place from had not taken everything with them. There was the usual assortment of snow shovels, coat hangers, and mostly empty bottles of cleaning products that come with any new move, but in my room, there was also a shelf of paperback books. Two of these books changed my life.

The first was called the Dark is Rising, a wonderful fantasy novel, the first of the genre I can remember reading. I re-read it recently for my children, and it still works, just head and shoulders above most of the genre, especially fantasies written for children. A book just soaked in mystery and ancient struggle, hidden inside the everyday world. Do read it.

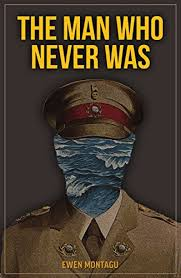

The second was called the Man who Never Was. In my memory, anyway, this book was all but falling apart, and there was a picture on the cover of a military uniform, but without a head, just a cap sitting jauntily above where the head should be. I assumed that this too was fiction, but it turned out to be real, and it's the story of the first large scale real-world deception that I had ever encountered. Fascination with deception underlies so much of my curiosity, my vision of the world, and this book was the first touchstone.

The book was written by a man named Ewen Montagu, sometime in the early 1950s. Montagu had been part of British Naval Intelligence during WWII. I found out more about him later, he was a lawyer in peacetime, generally respected, and he was given an important liaison role between the various intelligence services. He served on several committees and had access to more secret information than most of his peers. Intelligence, then and now, is heavily compartmentalized, so Montagu's position was uncommon, and shows the level of trust in which he was held. Is that the right way to write that? He had good pull, is what I'm trying to say.

One of the committees on which he served had been asked to help with deception operations to cover the upcoming Allied invasion of Italy. Quick chronological background there, this is late 1942, the invasion is scheduled for early spring 1943, April or May. The Allied forces plan to invade Sicily first from their bases in North Africa. Sicily is a pretty obvious landing spot, and they want to re-direct Axis attention to any other part of the Mediterranean that they can, to spread out the Axis forces along a wider front. Since the invasion involves so much naval activity, and Montagu's job involves naval counter-intelligence, he's asked to see what his group can do to spread disinformation into his Axis counterparts.

Someone at a committee meeting, Montagu doesn't identify him in the book, mentions an incident from earlier in 1942, where a British courier was shot down over Spain. The courier had been carrying important documents, real memoranda about upcoming Allied movements, and the Spanish authorities shared these with German intelligence, Spain being fairly pro-German. German intelligence, the British learned, discounted these documents as planted and spurious, but it showed that documents recovered in Spain would probably get to German intelligence, the target they were trying to deceive. So, suggested the unknown committee member, why don't they, the British, plant fake documents, documents with misleading information on the upcoming invasion, on a corpse and stage a crash on Spanish soil?

I learned later that this sort of operation has a name, it's called the Haversack ploy. The idea is that you send an agent with false information close to enemy lines. He appears to be surprised when he's spotted by enemy soldiers, and rides away quickly at speed, being chased all the while. As he rides away, he lets the haversack with the false information fall off his mount, tries to return for it, but has to leave it behind lest he be captured. His efforts to retrieve the haversack, and the drama of the chase, establish the information's bona fides in the enemy's mind, and the deception is accomplished.

So Montagu is asked to look into the practicalities of this much more complicated version of the Haversack ploy, whether a body can be found to suit their purposes, whether they can mimic a death by air crash successfully, whether the right spot can be found for the staged crash. This was the part of the book that truly gripped me, because every detail of the deception was planned with the elegance and thoroughness of staging a play. Montagu consults pathologists about what sort of corpse they need, whether the body needs to have seawater in the lungs, what sort of postmortem the Spanish authorities might order. He does eventually have to actually acquire a body from the morgue, with family permission, he's careful to note.

Then the correct sort of uniform needs to be prepared, convincing documentation, both official and private. Montagu invents a backstory for the body, Major Charles Martin of the Royal Marines, complete with personal letters, photos of a fiancee, ticket stubs from a night at the theater before the fictitious flight. One detail I never forgot is that Montagu himself put everything that the dead man would have had in his pockets into his own pockets for weeks, so that they would have the right patina of use and not seem incorrect. He took the fictitious letters and folded them and opened them for several hours, so that they would have the proper feel of well-used and much-examined paper. He rubbed the fake identity cards on his pants off and on for days to give them the right sheen.

They can't risk the fake documents coming detached from the body, they decide, so they acquire one of those briefcase chains that you see in cool thrillers, and tie it to the corpse's belt. They've decided that for practical reasons, they will release the body at sea near the Spanish coast, at the right time of night for the tides to wash it ashore. Montagu accompanies their gimmicked body to Gibraltar, where they put it on a submarine, sail secretly along Spain's coastline until they reach a river estuary, one with a town of fishermen who are sure to discover a body soon, and, a town that they know has a very active German spy in residence. The body is actually floated out of the submarine through a torpedo tube late at night as the tide turns, and they watch it begin to float to shore through a periscope. Can you make this up? Not easily.

The rest of the book deals with the details of the actual invasion, which was successful. The Allied armies landed on Sicily's southwestern coast, almost without resistance, as most of the Axis forces have been stationed to the east side of the island, where Montagu's documents had implied would be the main site of the landings. Montagu's packet had also implied strongly that there would be other landings on islands in Greece, and in Sardinia, and the Axis powers did position forces there to meet these imaginary threats, slowing and weakening their response to the true invasion.

Montagu mentions in the book that his operation cannot take sole or even primary credit for these events, since there were other deceptions at work, and the invasion was so large that no one group could claim credit. But his operation certainly didn't hurt matters. After the war the Allied powers conducted vast audits of German and Italian records about the conflict, to see what results had been produced by all their various operations. Montagu's Haversack ploy, which, by the way, was given the entertaining name Operation Mincemeat, was one of the most succesful tactical deceptions in the whole European theater.

Everything worked according to their hopes. The body was discovered that morning by fishermen, who brought it and its disinformation straight to the German agent. He had copied and transmitted the documents to German military intelligence by that evening, and they had prepared a summary for top-level officers by the next morning. The relief and the pleasure, Montagu says, which they felt at having hard evidence of Allied intentions in Italy was profound.

It was now the beginning of May 1943 and the Axis knew that any invasion along the Mediterranean coast would have to be soon. The head of German military intelligence, Admiral Canaris, personally requested the Spanish government provide his men with the actual documents to examine, not just photos or copies. By the middle of May, it seems, Hitler himself had been briefed on the discovery and had talked to Mussolini about how Sardinia, Corsica and Greece, the fake targets, needed to have their defenses strengthened. Even after the invasion of Sicily took place in July, the German armed forces acted as though they were a diversion from the real threat in Greece, even sending General Rommel to Greece to repulse the expected attack, which never came.

Normally in Great Britain, intelligence operations are kept secret for decades after the event. The British effort to crack the German Enigma code before and during WWII, for example, did not become public knowledge until the late 1970s. But Operation Mincemeat came out much earlier. A British official who knew of the operation wrote a spy novel where remarkably similar events form the plot, and Naval intelligence decided to have Montagu write some of the story of the real operation, to avoid further curiosity. Montagu does not include all the details which have since emerged about the operation, and by his own account, he wrote the whole book very quickly, in something like a week.

And I'm very grateful he did, because it is a powerful lesson in the psychology and mechanics of deception. Thinking through events from the target's point of view, noticing and disposing of every detail, and especially, especially, planting your deceptive information where your target is most desirous of discovering it. It's fairly clear now that the success of the operation was German intelligence's desire to produce a really big coup from their Spanish sources. They had made a great deal of investment in cultivating all possible intelligence sources in Spain, both official and unofficial, and they wanted that investment to show results. This is perhaps an inapt parallel, but it's similar to a problem that occurs in the psychology of stock traders, where they are overinvested in complex trades, ones that required a great deal of their research and attention, but which are not as productive as their simple bread and butter trades. By sending their disinformation into the heart of their target's expectations, Montagu's committee gave themselves the best chance not just of their deceit being accepted, but of having it be ACTED UPON. Which is the whole point, after all.

Toodle pip, Ben